The image (below) of what looks like the Pillsbury dough boy, with one foot on a cutting board, slicing into a roast while another knife has been stabbed through the meat to keep it in place, is very disturbing to me. And disgusting.

I have never been a person who ate much meat. Not that I was raised as a vegetarian, but I couldn’t really stomach the smell of it cooking in the house growing up. And this image brings back those odors and aversion. The idea that a dough boy/chef is included in this image is a mystery. Are they attempting to show a generic human? Someone unidentifiable? Or was that human form chosen to place the most emphasis on the actual meat? The knife holding the roast onto the board seems an extremely aggressive move, one that leaves me queasy. If I were to find the image while browsing online, I would quickly pass it like seeing something distasteful and immediately dismissing it from my mind and memory. If I were to guess, and it would be strictly a guess, I would say the image is a way of disassociating ourselves from where the meat came from, that it is ours to conquer, cook and devour. There is no reality as to where it came from, how the animal was treated while it was alive, how it died or how it came to be on this cutting board. Just as packaged meat in department stores are as far removed from the animal it came from as possible, so too this image is to me.

This last Christmas, we had four vegetarians, one vegan and two meat eaters at our table. All women and one man, my husband. The women decided to have vegetarian Indian cuisine and each of us made an Indian dish or two. I watched my husband push the food around on his plate and look rather suspiciously at it. The next day he asked, “What’s a guy have to do around here to find something to eat?” I laughed and responded, “Look in the refrigerator- lots of leftovers. Do you always have to have meat?” So I can honestly say the way to my man’s heart is through dead animals. He rarely will have a salad, leaves most green things on his plate but will readily and eagerly finish off chicken, turkey and the occasional red meat in a heartbeat.

My experiences with gendered foods, at least in my family, has made it clear that a carnivorous lifestyle is mainly male gendered while vegetarianism is female oriented. “(M)en, athletes and soldiers in particular, are associated with red meat and activity… whereas women are associated with vegetables and passivity” (Curtin). From my observation, there is also a generational difference. Most of my daughters friends, both male and female, are vegetarian or vegan. About half of my friends, in their 40s through 80s are carnivorous, I am one of the few vegetarian exceptions of my age. So I can’t say unequivocally that meat is male and salad is female, but I do see this trend in older people. However, very few millennials are carnivorous. Living in California, I have noticed that most men eat burritos with meat at Mexican restaurants and most women choose tacos. Size? Volume of food? Do men feel more manly eating an enormous burrito with their hands? Possibly.

Greta Gaard writes that vegetarianism in the west should be the go-to diet and meat is unnecessary. She sees all the “isms” as deeply connected to our contrived patriarchal system. “Speciesism is defined as the oppression of one species by another” and “is a form of oppression that parallels and reinforces other form(s) of oppression. These multiple systems — racism, classism, sexism, speciesism — are not merely linked, mutually reinforcing systems of oppression: they are different faces of the same system” (p20). Treating animals as void of emotional, physical or psychological feelings and fear is one way to continue the oppression and degradation. This holds true for animals as well as women. And Gaard rightly describes Bella the parakeet’s existence as lacking in her basic needs as a bird, leaving her lonely and listless. I’ve had birds and they bond to their owners like a child bonds with their mother. If you don’t have the time and understanding of how to care for a bird or any pet, not having one is probably a good move. Gaards description of having pets as oppression is interesting. I understand how she views that oppression, especially with more exotic, wild animals, but I have to disagree with her belief that owning dogs and cats is tantamount to slavery. I have four dogs (two rescues) and I appreciate and love them all for their uniqueness and personalities. “By keeping pets, we strive to shield ourselves from recognizing our own complicity in a system of inter-species domination” (p21). I will have to consider this as we move further into this course. I am, however, fully on board with ending the suffering of all animals, in zoos, shelters and farms. I am fully on board with ending factory farming of animals for meat. I am fully on board with ending animal testing. It is amoral, greed induced and causes extreme suffering. If we are intricately linked energetically, and I believe we are, how can we harm another living creature? The Dalai Lama’s definition of compassion is this: “He bases his teachings of compassion on Tibetan Buddhism. The Tibetan term for compassion is nying je, which… “connotes love, affection, kindness, gentleness, generosity of spirit and warm-heartedness.” People with these traits want to help others who suffer. If you look at the Latin roots of the word compassion, they are com, which means with, and pati, which means suffer. So, the word compassion literally means to suffer with…Compassion…opens our heart. Fear, anger, hatred narrow your mind… having compassion for others is a way to help people gain strength when facing issues with health and anxieties” (https://www.huffpost.com/entry/lessons-of-compassion-fro_b_7868940). When applied to all living creatures, compassion could save the world. Being a compassionate vegetarian feminist sounds like a role we should all engage in.

Deane Curtin states that “To choose one’s diet in a patriarchal culture is one way of politicizing an ethic of care. It marks a daily, bodily commitment to resist ideological pressures to conform to patriarchal standards, and to establishing contexts in which caring for can be non-abusive.” She also asks the reader to take into consideration location, class, economics, gender and climate in order to understand how some cultures cannot remove meat from their diet. Curtin’s moral vegetarianism allows for these exceptions. In Western cultures, however, “An ecofeminist perspective emphasizes that one’s body is oneself, and that by inflicting violence needlessly, one’s bodily self becomes a context for violence. One becomes violent by taking part in violent food practices. The ontological implication of a feminist ethic of care is that nonhuman animals should no longer count as food” (Curtin). This last statement has had a profound effect on my ‘indifferent’ attitude when it comes to meat eating. I have always been a firm believer that I am what I eat. If i eat meat, then, I am ingesting pain, fear, inhumanity and violence.

One of the more frightening movements, in my opinion, is genetically engineered (GE) animals. These are animals essentially grown in a lab. In particular, salmon grown by a company in Canada is unsure of the breeding capability. “(U)p to five percent of AAS salmon may be able to reproduce. If an escape of an AAS were to occur, interbreeding could occur with wild Atlantic salmon and some species of trout, which could lead to genetic contamination and other unpredictable ecological consequence” (Lee, p 68). There seems to be little acknowledgment regarding the dangers and unknowns of genetic animal engineering for food. And, as Lee reports, little response from these companies whose policies are opaque and not forthcoming. Ecofeminism, Lee states, can create a legal framework, different than the existing patriarchal one, that looks at the potential invasive and destructive possible outcomes of GE foods with nature. “Damaging (patriarchal) structures and mindsets constantly inform and maintain one another, making it difficult to uncover inherent biases, especially when they become codified in laws and policies that are justified as being “science- based”—the implication then being that they are objective and neutral” (Lee, p 70). Ecofeminism can challenge these systems.

Watching how quickly the Animal Kill Clock increases in the death toll of animals slaughtered for food has given me no appetite for meat, of any kind. Once I saw it broken down into how many types of animals and their numbers, I have decided to be dedicated to vegetarianism instead of my ‘flexitarianism’ I’ve used as an excuse for years. It made people laugh but I’m no longer laughing. I find it incredible and imperative that with new information regarding issues that significantly affect not just me but everyone, including nonhuman animals, I can change a lifetime of habit. Whether it’s from a compassionate or moral imperative point of view, or another entirely different stance, it is the right thing to do, for animals, for humans and for the planet.

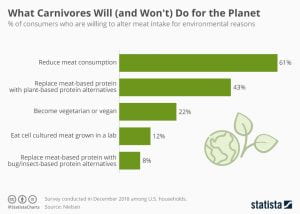

https://www.statista.com/chart/19135/environmnetal-meat-alternatives/

Annotated Bibliography

Lee, Angela. “An Ecofeminist Perspective on New Food Technologies.” Canadian Food Studies, Vol 5, No 1. University of Ottowa, February 2018. pp. 63-89.

Lee argues that science and technology cannot be automatically assumed to be for the greater good. From an ecofeminist perspective, she analyzes both the potential positive and negative effects GE animals may/will have in society. Looking at the root causes of hunger and food lack is a more appropriate direction than attempting to create an overabundance of meat as a fix-all approach. And disregarding the humanitarian and spiritual reasons for starvation do not address the issue, but digs us deeper into a quagmire of technological maybes.

Hello Tari. Reading your post this week got me to do a little bit of thinking. When you described how affected you were by the meat cutting image, my first reaction was that you were being silly and overreacting. Then I thought for a second about what separates me from the majority of this class. I’m a man. While I personally have never been particularly fond of the scent of cooking meat, I’ve never been bothered by it. But as a man cutting and eating (maybe even aggressively eating) meat is something I am encouraged to do on at least some level, so I think theres a good chance this image affects people more than I realize.

Your mention of men preferring bigger portions was interesting to me. My girlfriend and I regularly go to mexican places and usually she gets 3 tacos and I get a big burrito. I don’t know if I’ve ever felt manlier about eating what is effectively a big, thick sandwich but I have seen this scenario play out a lot with other couples as well, so maybe you are onto something.

As for Gaards statements, I agree with a lot of the spirit of what she is saying, but think putting it into practice is a very different story. You mentioned your rescue dogs, which makes sense, while Gaard is right in pointing out that our pets are 100% dependent on us and do not have many rights as individuals, neither do babies (though of course babies have constitutional protections in the United States that do not apply to non-human animals) and we don’t consider our children our slaves, though we do often consider our pets our children.

Hi Tari,

I read your post and two points that stood out to me. First let me say that I got very hungry while reading your post – the Indian cuisine you discussed as well as the photo of the food looks amazingly delish! I think this is a great way of swaying people toward plant-base diets.

I do agree with you on the “generational difference” when it comes to meat. I don’t remember any of my older loved ones (friends and family) not liking meat, in fact, a meal was not complete without it. Although Gaard made valid arguments about meat being tied to oppression of women, slavey, and so on, it is still a difficult thing for one to give up meat and the consumption of products relating to animals. However, I think we have to be able to unlearn what was imbedded into us from the older generation. And as such, this topic has opened my eyes – in that, it reminds me to think about what I’m really eating. The younger generation like you mentioned are way ahead of us in so many ways. But I also hope that education as to the treatment of animals connecting to what is on our plates is something more than a trend. If not, they are more likely to fall back into bad decisions in the food department as trends change.

You also pointed out having to “disagree with her (Gaard’s) belief that owning dogs and cats is tantamount to slavery.” I’m with you here as I have a dog to whom I love dearly. While it is understood that the relationship we have with our pets are “unequal” as Gaard stated, I do believe that that is ok as well. This is because recognition is key here! Being able to recognize that although my dog is my pet, she is also a dog and should be treated as such. Meaning having room to play, associate with other dogs, as well as have her own space to be happy then I don’t see the harm. Gerard also made the point that: “We somehow feel justified that as long as we keep captive and show kindness to one or the token species of animals, the others can be experimented on caged, tormented, eaten” (Gaard).

Though I disagree with some of this, her point is clear and somewhat true if we look at it with deeper lenses, so when it comes to food, everything circle’s back to eating something that once lived. However, when it comes to animals, I think two things need to be established and separated here; good healthy relationship with food, an animal/pet vs. a bad one. I am struggling with the fact that we as a species need to kill and eat, and whether our diets are plant or animal based, we still need to kill something in order to survive.

Mary

Hi Tari! What a thoughtful blog post. Looking at your chart at the end, I was intrigued by the term “cell-cultured meat grown in a lab.” This is a concept I was not familiar with whatsoever, so I researched it some more. As a Celiac, I cannot eat gluten. Most meat substitutions are made with some sort of wheat. I was vegetarian for many years, and relied heavily on meat substitutes. Once I was no longer able to eat them, I slowly found my way back to eating a “normal,” meat-filled diet. I didn’t know there was another way to create fake meat that was not plant based. So, this cell-cultured meat substitute is made from an animal cell, yet no animals are harmed in order to keep creating the meat. Apparently there are none currently available on the market, but researchers are hoping to roll it out soon. This is something I would definitely be willing to try, even though the concept weirds me out a little? Saying that though, i feel guilty. I hate that I am more weirded out by this less violent method of making meat than I am by just straight up eating meat. It shows how conditioned we are.

More info:

https://www.theguardian.com/food/2020/jan/19/cultured-meat-on-its-way-to-a-table-near-you-cultivated-cells-farming-society-ethics

Hey Tari

The way you described your husband made me feel like I am being told about the stereotypical patriarch’s eating habits in a sitcom. I wonder how much of this gender based preference for food is genetic and how much is from societal influence. I think back to my eating habits as a little boy and I was picky about everything, vegetables and meat alike. Even now as I have expanded my pallet, I find myself turned off by especially carnal meat, like a rare juicy steak and bone in chicken. I love chicken tenders and beef cooked a good amount, although not well done because it doesn’t make me feel like am eating a dead animal. It’s got to be out of sight out of mind or else I get kind of grossed out.

I wanted to look at our dietary decisions for a nutritional standpoint. Meat is packed with protein, but when it comes down to it, “Body size is the main difference between the needs of males and females” (Harvard). Men do not need meat in their diet because of a genetic requirement to go towards meat instead of vegetables. The only reason a man should be eating more meat than a woman is because he may be larger than said woman so he needs more proportionately. Interestingly, woman need more iron in their diet due to their menstrual cycle than men do, so they have a valid claim to eating more beef than men.

I think I world without any pets would be a much less fulfilling reality than what we enjoy now. Expecting people not to have pets is a tall order, and I think Gaard knows this which is why she says we should “limit or forego relationships with other species as pets, and live instead with the longing for wild animal companions.” I think the choice to not just say forego is powerful, because I do not see people giving up pet-ownership easily at all, although many people could understand the compassion that Gaard has for Bella and use that to reconsider the power dynamic that we are so used to.

https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/good-nutrition-should-guidelines-differ-for-men-and-women