The image (below) of what looks like the Pillsbury dough boy, with one foot on a cutting board, slicing into a roast while another knife has been stabbed through the meat to keep it in place, is very disturbing to me. And disgusting.

I have never been a person who ate much meat. Not that I was raised as a vegetarian, but I couldn’t really stomach the smell of it cooking in the house growing up. And this image brings back those odors and aversion. The idea that a dough boy/chef is included in this image is a mystery. Are they attempting to show a generic human? Someone unidentifiable? Or was that human form chosen to place the most emphasis on the actual meat? The knife holding the roast onto the board seems an extremely aggressive move, one that leaves me queasy. If I were to find the image while browsing online, I would quickly pass it like seeing something distasteful and immediately dismissing it from my mind and memory. If I were to guess, and it would be strictly a guess, I would say the image is a way of disassociating ourselves from where the meat came from, that it is ours to conquer, cook and devour. There is no reality as to where it came from, how the animal was treated while it was alive, how it died or how it came to be on this cutting board. Just as packaged meat in department stores are as far removed from the animal it came from as possible, so too this image is to me.

This last Christmas, we had four vegetarians, one vegan and two meat eaters at our table. All women and one man, my husband. The women decided to have vegetarian Indian cuisine and each of us made an Indian dish or two. I watched my husband push the food around on his plate and look rather suspiciously at it. The next day he asked, “What’s a guy have to do around here to find something to eat?” I laughed and responded, “Look in the refrigerator- lots of leftovers. Do you always have to have meat?” So I can honestly say the way to my man’s heart is through dead animals. He rarely will have a salad, leaves most green things on his plate but will readily and eagerly finish off chicken, turkey and the occasional red meat in a heartbeat.

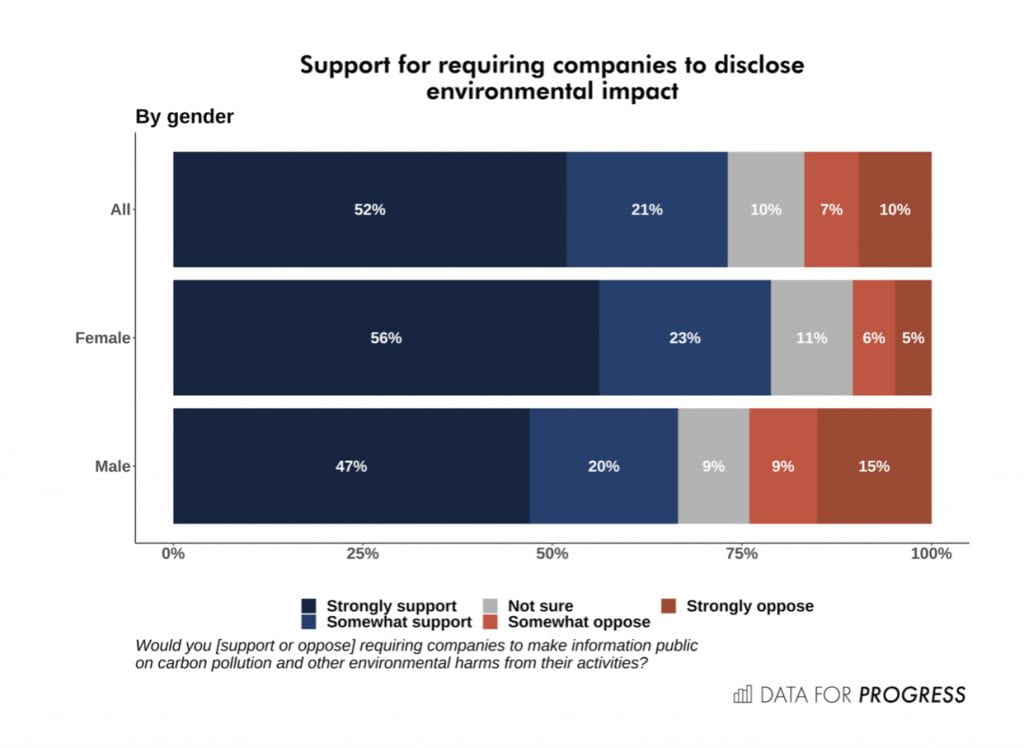

My experiences with gendered foods, at least in my family, has made it clear that a carnivorous lifestyle is mainly male gendered while vegetarianism is female oriented. “(M)en, athletes and soldiers in particular, are associated with red meat and activity… whereas women are associated with vegetables and passivity” (Curtin). From my observation, there is also a generational difference. Most of my daughters friends, both male and female, are vegetarian or vegan. About half of my friends, in their 40s through 80s are carnivorous, I am one of the few vegetarian exceptions of my age. So I can’t say unequivocally that meat is male and salad is female, but I do see this trend in older people. However, very few millennials are carnivorous. Living in California, I have noticed that most men eat burritos with meat at Mexican restaurants and most women choose tacos. Size? Volume of food? Do men feel more manly eating an enormous burrito with their hands? Possibly.

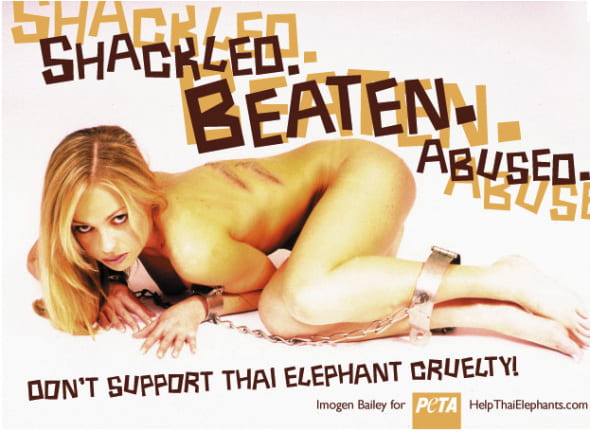

Greta Gaard writes that vegetarianism in the west should be the go-to diet and meat is unnecessary. She sees all the “isms” as deeply connected to our contrived patriarchal system. “Speciesism is defined as the oppression of one species by another” and “is a form of oppression that parallels and reinforces other form(s) of oppression. These multiple systems — racism, classism, sexism, speciesism — are not merely linked, mutually reinforcing systems of oppression: they are different faces of the same system” (p20). Treating animals as void of emotional, physical or psychological feelings and fear is one way to continue the oppression and degradation. This holds true for animals as well as women. And Gaard rightly describes Bella the parakeet’s existence as lacking in her basic needs as a bird, leaving her lonely and listless. I’ve had birds and they bond to their owners like a child bonds with their mother. If you don’t have the time and understanding of how to care for a bird or any pet, not having one is probably a good move. Gaards description of having pets as oppression is interesting. I understand how she views that oppression, especially with more exotic, wild animals, but I have to disagree with her belief that owning dogs and cats is tantamount to slavery. I have four dogs (two rescues) and I appreciate and love them all for their uniqueness and personalities. “By keeping pets, we strive to shield ourselves from recognizing our own complicity in a system of inter-species domination” (p21). I will have to consider this as we move further into this course. I am, however, fully on board with ending the suffering of all animals, in zoos, shelters and farms. I am fully on board with ending factory farming of animals for meat. I am fully on board with ending animal testing. It is amoral, greed induced and causes extreme suffering. If we are intricately linked energetically, and I believe we are, how can we harm another living creature? The Dalai Lama’s definition of compassion is this: “He bases his teachings of compassion on Tibetan Buddhism. The Tibetan term for compassion is nying je, which… “connotes love, affection, kindness, gentleness, generosity of spirit and warm-heartedness.” People with these traits want to help others who suffer. If you look at the Latin roots of the word compassion, they are com, which means with, and pati, which means suffer. So, the word compassion literally means to suffer with…Compassion…opens our heart. Fear, anger, hatred narrow your mind… having compassion for others is a way to help people gain strength when facing issues with health and anxieties” (https://www.huffpost.com/entry/lessons-of-compassion-fro_b_7868940). When applied to all living creatures, compassion could save the world. Being a compassionate vegetarian feminist sounds like a role we should all engage in.

Deane Curtin states that “To choose one’s diet in a patriarchal culture is one way of politicizing an ethic of care. It marks a daily, bodily commitment to resist ideological pressures to conform to patriarchal standards, and to establishing contexts in which caring for can be non-abusive.” She also asks the reader to take into consideration location, class, economics, gender and climate in order to understand how some cultures cannot remove meat from their diet. Curtin’s moral vegetarianism allows for these exceptions. In Western cultures, however, “An ecofeminist perspective emphasizes that one’s body is oneself, and that by inflicting violence needlessly, one’s bodily self becomes a context for violence. One becomes violent by taking part in violent food practices. The ontological implication of a feminist ethic of care is that nonhuman animals should no longer count as food” (Curtin). This last statement has had a profound effect on my ‘indifferent’ attitude when it comes to meat eating. I have always been a firm believer that I am what I eat. If i eat meat, then, I am ingesting pain, fear, inhumanity and violence.

One of the more frightening movements, in my opinion, is genetically engineered (GE) animals. These are animals essentially grown in a lab. In particular, salmon grown by a company in Canada is unsure of the breeding capability. “(U)p to five percent of AAS salmon may be able to reproduce. If an escape of an AAS were to occur, interbreeding could occur with wild Atlantic salmon and some species of trout, which could lead to genetic contamination and other unpredictable ecological consequence” (Lee, p 68). There seems to be little acknowledgment regarding the dangers and unknowns of genetic animal engineering for food. And, as Lee reports, little response from these companies whose policies are opaque and not forthcoming. Ecofeminism, Lee states, can create a legal framework, different than the existing patriarchal one, that looks at the potential invasive and destructive possible outcomes of GE foods with nature. “Damaging (patriarchal) structures and mindsets constantly inform and maintain one another, making it difficult to uncover inherent biases, especially when they become codified in laws and policies that are justified as being “science- based”—the implication then being that they are objective and neutral” (Lee, p 70). Ecofeminism can challenge these systems.

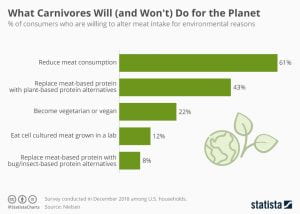

Watching how quickly the Animal Kill Clock increases in the death toll of animals slaughtered for food has given me no appetite for meat, of any kind. Once I saw it broken down into how many types of animals and their numbers, I have decided to be dedicated to vegetarianism instead of my ‘flexitarianism’ I’ve used as an excuse for years. It made people laugh but I’m no longer laughing. I find it incredible and imperative that with new information regarding issues that significantly affect not just me but everyone, including nonhuman animals, I can change a lifetime of habit. Whether it’s from a compassionate or moral imperative point of view, or another entirely different stance, it is the right thing to do, for animals, for humans and for the planet.

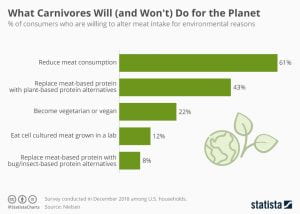

https://www.statista.com/chart/19135/environmnetal-meat-alternatives/

Annotated Bibliography

Lee, Angela. “An Ecofeminist Perspective on New Food Technologies.” Canadian Food Studies, Vol 5, No 1. University of Ottowa, February 2018. pp. 63-89.

Lee argues that science and technology cannot be automatically assumed to be for the greater good. From an ecofeminist perspective, she analyzes both the potential positive and negative effects GE animals may/will have in society. Looking at the root causes of hunger and food lack is a more appropriate direction than attempting to create an overabundance of meat as a fix-all approach. And disregarding the humanitarian and spiritual reasons for starvation do not address the issue, but digs us deeper into a quagmire of technological maybes.

e that I will be posting the suggestion of sharing abundant crops and gathering a consensus on when and how often to meet. Our neighborhood has bountiful orange, grapefruit, lemon and lime trees along with avocado trees. We have two avocado trees that produce continual, enormous, copious avocados. I have been sharing them with neighbors and friends, but will be able to include them in our veggie swap gatherings.

e that I will be posting the suggestion of sharing abundant crops and gathering a consensus on when and how often to meet. Our neighborhood has bountiful orange, grapefruit, lemon and lime trees along with avocado trees. We have two avocado trees that produce continual, enormous, copious avocados. I have been sharing them with neighbors and friends, but will be able to include them in our veggie swap gatherings.